Hearing Catherine

Felicity Ford is an artist working principally with sounds and textiles. She is especially interested in women’s lives and history, and her work mainly investigates domestic themes and materials. Completing her PhD on The Domestic Soundscape in 2011, she has since worked on projects for organisations that include the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture; The Wellcome Library); TATE Modern and The Museum of Oxford. She is currently working on a series of sound pieces to represent Catherine Dickens in the Charles Dickens Museum. Felicity lives in Reading with her fiancée Mark, three naughty ducks and a very spoiled cat known as ‘Joey Muffkins’.

By Felicity Ford

I’m working on a set of sound pieces for the Charles Dickens Museum. The sound pieces are part of an Arts Council funded Art Project for their forthcoming exhibition, The Other Dickens about the life of Charles Dickens’s wife, Catherine. I am composing them from recordings that draw on what we know about Catherine’s life, and which are designed to give presence and texture to her memory. In my research I’m listening out for material evidence of Catherine; for the sounds of places where she spent time; the words she exchanged in letters with loved ones; the technology and labour that defined her domestic soundscape; and the literature and music she would have heard in daily life.

My project is called Hearing Catherine.

Making Catherine's recipe for Mutton Broth © Felicity Ford, used with kind permission.

A voice in the past

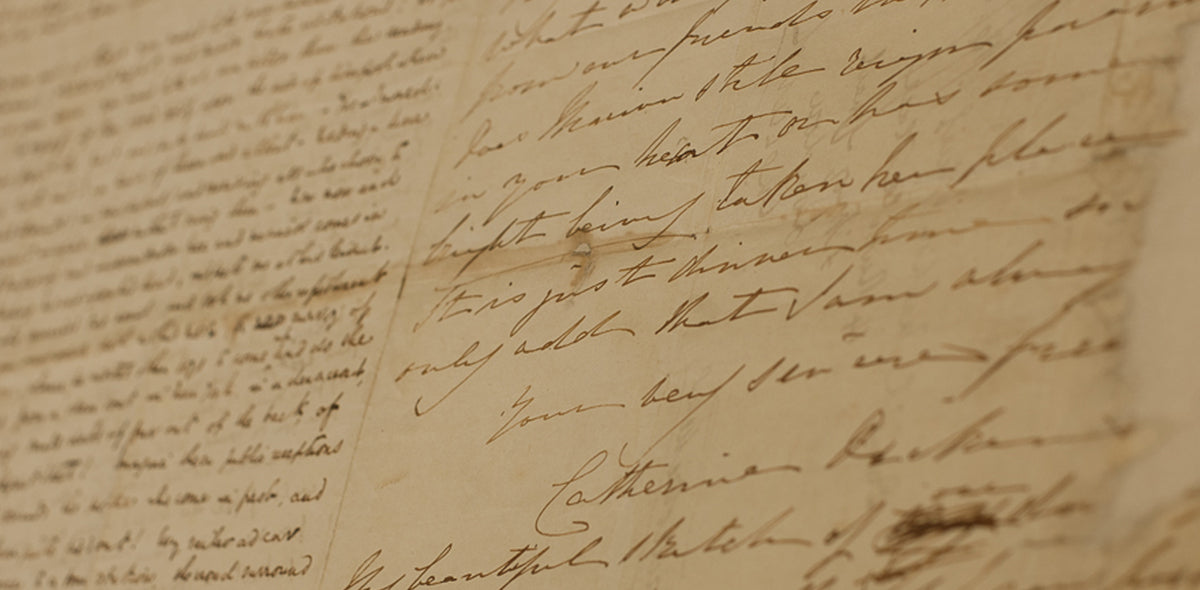

Charles burned Catherine’s letters to him after their separation in 1858 so we cannot read about their relationship in her words. However luckily Catherine can be ‘heard’ elsewhere; in correspondence with friends and family; in letters by Charles to which she contributed; and in a cookbook she wrote which was published under the pseudonym ‘Lady Maria Clutterbuck’.

These resources apprehend Catherine in her own light. They are meticulously catalogued in the fantastic tome written by the guest curator for the exhibition, Lillian Nayder: The Other Dickens, A life of Catherine Hogarth. This book took Lillian a decade to write and research and, in its pages, Catherine emerges as vibrant, competent and loving.

Lillian’s painstaking research gives context to Catherine’s life, explaining the status of women in Victorian marriages and society, and giving crucial insights into the legal and economic disadvantages faced by Catherine and her contemporaries. In Victorian times a woman gave up her legal identity upon being married; the children from marriage automatically belonged to the husband; and pain relief during childbirth was seen by some to contravene birth’s function as God’s punishment on womankind for Eve’s transgression in the Garden of Eden. Reading in this historic context, the evidence amassed and organised by Lillian recuperates Catherine as a real person who stands in stark contrast to the caricature of feminine failure conjured by Charles Dickens in the stories he circulated at the time of the couple’s separation.

Catherine's words © Felicity Ford, used with kind permission.

Authorship

On a practical level, Lillian’s book is a road-map to Catherine’s life, leading to many key documents and publications. The references point to musical works, female friendships and correspondence in which Catherine herself can be detected. I’ve found compositions published by George Hogarth - Catherine’s Father - which Catherine would certainly have heard, and musicians such as Abby Hutchinson of the Hutchinson Family Singers with whom Catherine was friends. I’ve also tracked down an old picture book that Catherine kept in her drawing room after her separation from Charles, and from which she read to her grandchildren. Clues about Catherine’s upbringing in New Town, Edinburgh, point to the kind of accent Catherine may have had, and have helped me to identify an appropriate voice actor with whom to bring some of Catherine’s written words to life.

On a slightly more conceptual level, Lillian’s scholarship recovers Catherine by going back to raw source materials – the actual letters and objects that were hers in real life. I am similarly drawn to raw source materials – to the things that Catherine herself would have touched and used and heard – in my quest to ‘hear’ her for the sound-pieces. I’ve been playing the piano in the same room at Doughty Street where she would have played the piano, and I spent last week familiarising myself with the type of Victorian range on which the recipes in her cookbook would have been prepared. I have cooked some of the recipes from that book, wondering in the process if I was hearing something similar to what Catherine heard when she penned the recipes in her sensibly titled book, What Shall We Have For Dinner?

However perhaps Lillian’s book is most inspiring to me in terms of its broader implications for how women might be reclaimed from history.

Playing the piano at Doughty Street © Felicity Ford, used with kind permission.

Reclaiming women from history (his story)

Like Catherine, many women have lost their voices to history.

However because Catherine’s husband was an absurdly famous novelist – and a particularly controlling person – the contrast between his power to tell Catherine’s story with her power to tell it, is extremely striking. Catherine’s story was so subsumed by the narrative talents of her husband that subsequent scholars of Dickens have relied on his word over hers in all the retellings, without returning to original sources to critically evaluate the evidence. In her redemptive book, Lillian does re-examine the evidence. Challenging the authority of Charles Dickens and his stories, she unearths Catherine, offering a freshly revised and complex version of events - A Life rather than The Life of Catherine Dickens, née Catherine Hogarth.

This aspect of the book – the care and love with which Lillian has reclaimed Catherine – has struck a very deep chord with me not just because it has given us a new way of perceiving Catherine Dickens herself, but because it models a hopeful template for retrieving all the women from history whose own times or circumstances did not enable them to leave their story behind.

A working Victorian range and all its sounds © Felicity Ford, used with kind permission.

International Women’s Day

On today, International Women’s Day, I find myself hoping that in returning to original sources; in straining to hear what Catherine heard; and in attending this project with some of the same care that Lillian has lavished on the subject, I can create sound pieces that reveal some of the traces of Catherine I heard in Lillian’s book.

How we treat Catherine’s story is important, because her story is our history. Or, as Lillian Nayder writes:

We may be closer to the Victorians than we think. The persistent willingness of women to see themselves as subordinate and commonplace, and the varied ways in which they are encouraged to do so in our culture, suggest our proximity to Catherine and her contemporaries.

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog