Scandal at Staplehurst?

Morgan Leeson is a summer intern at the Charles Dickens Museum and a sophomore studying English at Bates College, located in Lewiston, Maine, U.S.A.

By Morgan Leeson

Raised on a diet of People magazines and Facebook scandals, I’ve always had a typically-millennial appetite for gossip. Based on this (admittedly shameful) drive, I’ve decided to research the Staplehurst Railway Crash for this week’s blog post, a tragic accident that incidentally threatened to expose Dickens’s affair with the young actress, Ellen Ternan.

On 9th June 1865, the Tidal Express Service was travelling from the French city of Bolougne to London, carrying 110 passengers. Among these passengers were Charles Dickens, aged 53, Ellen Ternan, and her mother, Frances, all of whom were returning from a holiday in France.

That same day, workmen had started to replace the supporting rails of a viaduct, over which Dickens’ train was scheduled to pass. The crew had received the go-ahead for construction from the project’s foreman, who had misread that day’s timetable, reporting no departing trains until much later in the day.

As a result of this mistake, workers were midway through the project when the train passed over the disassembled viaduct, at a speed exceeding 50mph. As Claire Tomalin describes in her 1990’s book, The Invisible Woman, the train “simply steamed over the gap, its middle section collapsing into it; some of the coaches then ran out of control down a bank and overturned into boggy ground, crushing and killing passengers.”

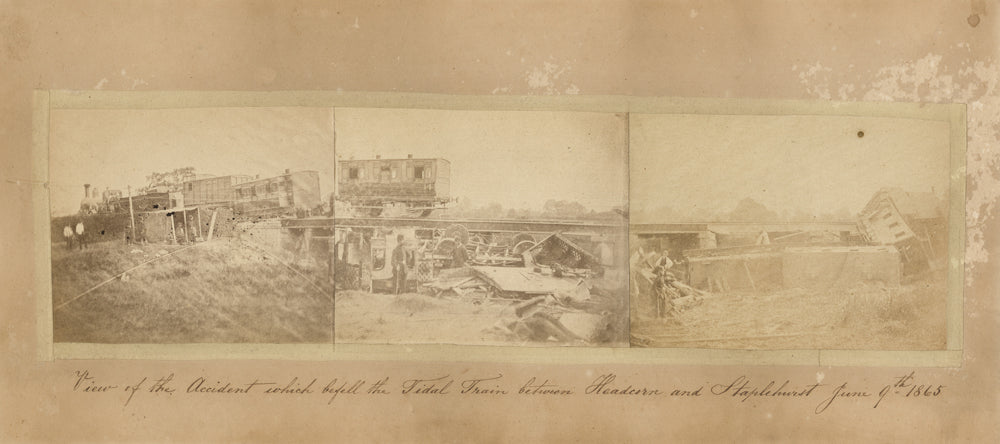

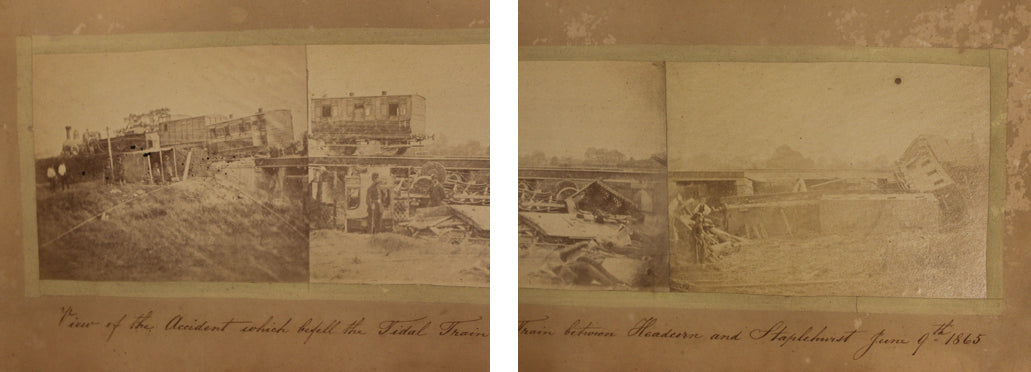

The aftermath of the crash can be seen in a series of three sepia-toned photographs, currently on display in the Mary Hogarth room at the Museum. The photographs have been mounted together to create a panorama of the scene, heightening our sense of how horrific the accident truly was. All in all, the crash resulted in 10 deaths and 50 injuries.

Facsimiles depicting the Staplehurst railway crash, located in the Mary Hogarth room. Charles Dickens Museum.

The original photographs with an inscription below, which reads “View of the accident which befell the Tidal Train between Headcorn and Staplehurst June 9th, 1865.” Charles Dickens Museum collection,DH753.

Close-ups of the original photographs. Charles Dickens Museum collection,DH753.

Due to the momentum of the train, Dickens’ passenger car was pulled off of the track, so that it dangled from the viaduct at a precarious angle. Fortunately, however, it was the only passenger carriage to remain on the bridge, which allowed passengers to climb to safety once the car had steadied. After escaping the cart, Dickens sprang into action, assisting passenger caught in the destruction below. Dickens describes the scene of the crash in an August 16th letter to Madame Viardot, writing: “the scene was so affecting when I helped in getting out the wounded and dead, that for a little while afterwards, I felt shaken by the remembrance of it.”

An illustration showing Charles Dickens at the site of the accident, assisting an injured passenger. Charles Dickens Museum.

However, despite Dickens’ heroism, his name was rarely mentioned in newspaper reports immediately following the accident. This is surprising given his exemplary relief work, as well as his celebrity status. Additionally, Dickens’ name was never brought up in planning for the accident’s inquest, which was unusual, according to scholar Lee D. Andrews, “considering [Dickens’] post-crash work on the scene and his good view from the front carriage.” Why then, was Dickens name left out of both newspaper reports and legal proceedings?

Today, most scholars believe Dickens tried to hide his involvement in the crash in order to keep his travels with Ellen Ternan a secret. By this time, Ellen had likely become Dickens’ mistress, and if the public were to discover the two travelling together, rumours would begin to circulate about the nature of their relationship. Thus, in the months to follow, Ellen was to stay tucked away in her home, slowly recovering from an injury to the upper left arm she had sustained during the crash. During this time, Dickens wrote Ellen many letters, jokingly nicknaming her “The Patient.”

As I researched the Staplehurst Railway crash for this post, I also stumbled across a note Dickens had written to his servant, John Thompson, during Ellen’s recovery period. Addressing Thompson, Dickens asks him to send “Miss Ellen tomorrow morning, a little basket of fresh fruit, a jar of clotted cream from Tuckers, and a chicken, a pair of pigeons, or some nice little bird.”

A portrait of Ellen Ternan as a young woman. Charles Dickens Museum Collection.

This little note, brimming with affection and care, gave me a greater appreciation for Dickens’ relationship with Ellen, as something more substantial than the OK! scandal I had initially expected. In fact, the relationship appears to have been much more than a disreputable fling, with the couple staying together until Dickens’ death on June 9, 1870, five years to the day of the Staplehurst Railway crash.

Further Reading:

Claire Tomalin, The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens (London: Viking, 1990).

Michael Slater, The Great Charles Dickens Scandal (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog