The Old Curiosity Shop: A Genuine Fake by Lee Jackson

Old Curiosity Shop c.1920-1940, A.032.12 © Charles Dickens Museum

‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ sits at 14 Portsmouth Street, on the south-western corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. It is a quaint wood-beamed cottage, with an upper floor that slightly overhangs the pavement, like a piece of Tudor England dropped into the twenty-first century. It may well be one of the oldest surviving buildings in central London and has been a place of literary pilgrimage for Dickensians since the 1880s. The masonry bears an inscription in Gothic lettering:

It is also, frankly, something of a fake.

Of course, this peculiar old building was known to Charles Dickens. It was near to the Insolvency Debtors Court which features in The Pickwick Papers and Little Dorrit; and it sits within the legal quarter of London portrayed in Bleak House. One can even glimpse Portsmouth Street from the chambers in Lincoln’s Inn Fields that once belonged to John Forster, Dickens’s friend and lawyer. Nonetheless, there is nothing within the book The Old Curiosity Shop (published in 1840), nor in Dickens’s correspondence, which suggests this was the ‘original’ of Dickens’s antique shop (several other sites have been suggested over the years). Dickens’s novel concludes with the author stating, that the titular shop ‘had long been pulled down, and a fine broad road was in its place’ – which one might think would settle the matter. And yet, in the late-Victorian and Edwardian era, this was the venue for visiting tourists, hoping to glimpse ‘Dickens’s London’.

How, then, did this place become so well-known?

There is every reason to trust a letter by Charles Tesseyman, which was published in the Echo, a popular London evening paper, on 31 December 1883:

"My brother, who occupied No.14 Portsmouth-street between 1868 and 1877, the year of his decease, had the words ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ placed over the front for purely business purposes, as likely to attract custom to his shop, he being a dealer in books, paintings, old china, &c. Before 1868 – that is, before my brother had the words put up – no suggestion had ever been made that the place was the veritable ‘Old Curiosity Shop’ immortalised in Dickens."

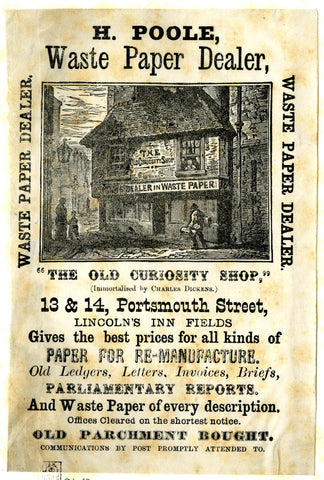

But, even as Tesseyman made this admission, it was already too late. The sign had been noticed by an American journalist, B.E. Martin, who published a literary tour of Dickens’s London in Scribner’s Monthly in May 1881. Martin admitted the connection to Dickens was ‘a fable … a pleasing delusion’, but the article nonetheless contained a sketch of the quaint old building – and tourists soon began to search for it. When Martin published his article, the shop did not even possess the second assertive line of writing, ‘Immortalised by Charles Dickens’ (the text was ‘The Old Curiosity Shop: Dealer in Works of Art’, as shown in a painting from 1879). But growing numbers of American tourists began to appear in Portsmouth Street and ‘Immortalized by Charles Dickens’ was added for good measure. This was probably the work of H. Poole, a dealer in waste paper, who owned the property in the 1880s and 1890s.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The shop’s celebrity dramatically increased in late-1883, when a series of press articles reported that it was under threat of demolition, after a neighbouring building had partially collapsed. The Daily Telegraph inaccurately claimed that the site was ‘long popularly identified with the “Old Curiosity Shop”’ and noted the irony of the threat of demolition coming at such a season (‘of all times in the year, seeing what DICKENS did for Christmas’). American collectors of Dickensiana were purportedly ‘quite ready to purchase the ruins, and fix them up in Boston or Philadelphia’, while others demanded loose bricks as mementoes. Such was the shop’s new-found fame that a stage version of The Old Curiosity Shop, scripted by Charles Dickens Jnr., already in pre-production at the Opera Comique hastily introduced and advertised a painting of the Portsmouth Street shop as the backdrop to one of the scenes. Meanwhile, more reporters, sketch artists and photographers lined up outside to record this piece of ‘Dickens’s London’ before it vanished.

And yet it never did.

The building did not collapse like the neighbouring property, nor was it swallowed up by subsequent nearby improvement works, which created the Parisian-style boulevards of Kingsway and Aldwych (although said works did destroy the genuine ‘original’ of Poll Sweedlepipe’s barber shop, from Martin Chuzzlewit, on nearby Kingsgate Street). Rather, the media hype, and subsequent guidebooks and articles, simply attracted more and more tourists. The building’s timbered exterior was also a good fit with the Victorians’ growing fascination with the Elizabethan Age. By the early 1900s there were ‘waggonettes laden with visitors … constantly arriving to see the curious little house’. The shop sold a variety of Dickens souvenirs, from postcards to presentation copies of Dickens’s complete works (which were shipped back to the United States for American tourists, to greet them on their return home). The shop became the place for Dickensian tourism; its authenticity was almost irrelevant – everyone went there and it had become emblematic of ‘Dickens’s London’.

By the 1930s, ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ was essentially a Dickens-themed gift and general antiques shop, aimed at tourists (with a sister gift-shop beside Anne Hathaway’s cottage at Stratford-upon-Avon). Though the shop itself was never bought up by wealthy Americans, there was a full-size recreation at the ‘Merrie England’ display at the Chicago ‘Century of Progress’ Exposition in 1933, and at several subsequent American expositions. Literary tourists now find that the shop sells unusual designer shoes, not Dickensian merchandise.

Old Curiosity Shop Commemorative Mustard Pot and Certificate,

DH859 © Charles Dickens Museum

The trade in Dickens memorabilia was abandoned in the 1990s when the local authority forbade Lincoln’s Inn Fields to coach parties (the modern equivalent of ‘waggonettes laden with visitors’). But tourists still come in dribs and drabs and ‘The Old Curiosity Shop: Immortalized by Charles Dickens’ now appears on Instagram or Twitter instead of picture postcards – and it still looks the part.

Lee Jackson is an author and historian, well-known for his website of primary sources www.victorianlondon.org, his guide to 'Walking Dickens’ London' (2012), 'Dirty Old London' (Yale, 2014) and 'Palaces of Pleasure' (Yale, 2019) examining nineteenth century mass entertainment. He is currently pursuing a PhD on ‘Dickensland’.

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog