Two Literary Titans Unite at Gad’s Hill

Morgan Leeson is a summer intern at the Charles Dickens Museum and a sophomore studying English at Bates College, located in Lewiston, Maine, U.S.A.

By Morgan Leeson

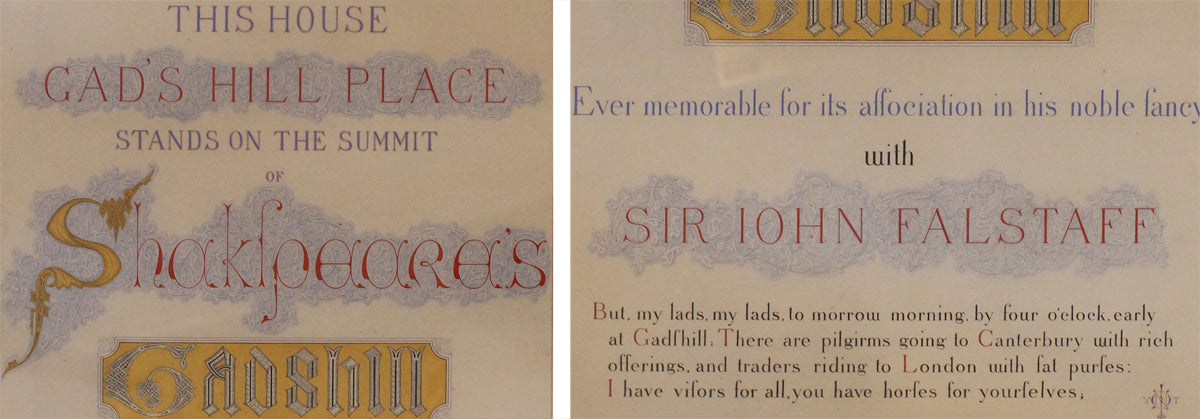

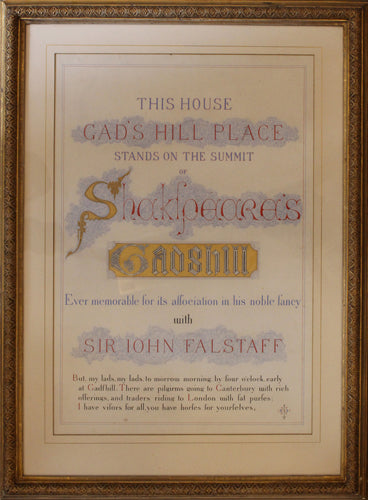

As visitors begin their journey through the Charles Dickens Museum, they are greeted in the entrance hallway by an illuminated inscription paying tribute to Gad’s Hill, Dickens’s final home, and its connection to the famous Shakespearean character Falstaff. Guests should be cheered to know that the inscription would have also welcomed visitors into Dickens’s “little Kentish freehold” from 1857, when Dickens commissioned the inscription, until his death in 1870. These guests included many notable authors of the day, such as Hans Christian Andersen, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Wilkie Collins.

The Gad’s Hill illuminated inscription, seen here in full. Charles Dickens Museum collection,DH82.

From his early childhood, Dickens had dreamed of owning Gad’s Hill Place. Passing by the mansion as a young child, Charles’ father, John Dickens, told the then nine-year-old Charles that, if he worked hard, he could one day own the Gad’s Hill property. Years later, after amassing critical success, Dickens discovered that the house was up for sale, and decided to purchase the property in March of 1856. Shortly thereafter, Dickens commissioned artist Owen Jones, to complete the commemorative illuminated inscription.

Only five years earlier, Owens had played an integral role in the creation of the Crystal Palace, displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851. In charge of the Palace’s interior design, Jones opted to decorate the space with bold, graphic patterns and primary colours. Additionally, Jones is known for his role in starting the Victoria and Albert Museum, designing some of the museum’s first galleries.

Photograph of Charles Dickens reading “A Vol. of French Revolut[ion]” in August of 1866, taken at the back of Gad’s Hill. Charles Dickens Museum collection,DH526

The inscription, intricately completed with red, blue, black, and gold ink, reads: “This house Gad’s Hill Place stands on the summit of Shakespeare’s Gadshill, ever memorable for its association in his noble fancy with Sir John Falstaff. But, my lads, my lads, to morrow morning, by four o’clock, early at Gadshill: There are pilgirms going to Canterbury with rich offerings, and traders riding to London with fat purses: I have visors for all, you have horses for yourselves.”

Charles Dickens Museum collection,DH82.

In the first half of the inscription, Dickens declares that his home “stands on the summit of Shakespeare’s Gadshill.” Although Shakespeare himself never lived on the property, Dickens is able to claim the estate stands atop “Shakespeare’s Gadhill” because of a reference Shakespeare had made to the home in Henry IV, Part I. In the play, one of the principal characters, Falstaff, makes plans to meet at Gad’s Hill Place with Prince Hal and Poins, before enacting their highway robbery plot.

Although Gad’s Hill is only briefly mentioned in the text, Dickens requests that the property be called “Shakespeare’s Gadshill” in the inscription. In doing so, Dickens draws a strong parallel between himself and Shakespeare, perhaps in an attempt to place himself within the shadow of Shakespeare’s legacy. This comparison, between Shakespeare and Dickens, was not unheard of at the time, particularly given their shared reputations as “writers of the people.” In fact, it could be argued that, by the time he moved to Gad’s Hill, Dickens had already earned this comparison, having penned some of his greatest novels, including The Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, and Bleak House.

Furthermore, Dickens was well acquainted with Falstaff through both his professional and personal worlds. As part of his professional life, Dickens staged an 1848 benefit production of The Merry Wives of Windsor, which featured Falstaff as a foolish suitor. In the production, Mark Lemon, close friend to Dickens and editor of Punch magazine, took on the role of Falstaff, while Dickens himself played Justice Shallow. On a more personal note, Dickens was reminded of Falstaff on a day-to-day basis, thanks to frequent visits to a neighbourhood pub, The Falstaff Inn.

Mark Lemon in the role of Falstaff, Charles Dickens Museum collection.

Mark Lemon in the role of Falstaff, Charles Dickens Museum collection.

However, despite Jones’ reputation as a ground-breaking artist, as well as Dickens’ reputation as a perfectionist, the piece contains a decidedly human flaw. Eagle-eyed visitors will notice the spelling mistake in the second-to-last line of the inscription, where “pilgrims” has been written as “pilgirms.” Whether or not Dickens noticed the misspelling we don’t know; regardless, the error serves as a good reminder that even the successful, like Dickens and Jones, make mistakes.

A close-up image of the spelling mistake. Charles Dickens Museum collection,DH82.

Further reading:

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog

![Photograph of Charles Dickens reading “A Vol. of French Revolut[ion]”](http://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0925/3888/files/DH526_R1.JPG?13226101506173074936)