Where did Dickens go to the toilet? by Louisa Price

This Saturday marks World Toilet Day, an important time to reflect on something many of us take for granted: running water and the removal of waste from our daily lives. We are often confronted with these matters when we peer into the past. At 48 Doughty Street we are regularly asked about how water and waste was dealt with by the Dickens family in the 1830s: Where did Dickens go to the loo? How did the family bathe? Did they have running water? This blog post is an attempt to address some of those questions.

Charles Dickens’s commode (a chair with a concealed chamber pot), Charles Dickens Museum collection

Space won’t permit me to tell many of the fascinating stories associated with sanitation in Victorian London. I won’t be able to tell you about the pollution problems of the great metropolis which caused William Cobbett to liken the city to a cyst on the face of the country. The cholera outbreaks and John Snow’s pioneering work which pinned the problem to water contamination will also not be covered here. I won’t be able to talk about the brilliance of Joseph Bazalgette, his 1860s sewer system and the creation of the Thames Embankment. If these are topics you wish to delve into further, I thoroughly recommend the book, Dirty Old London by Lee Jackson.

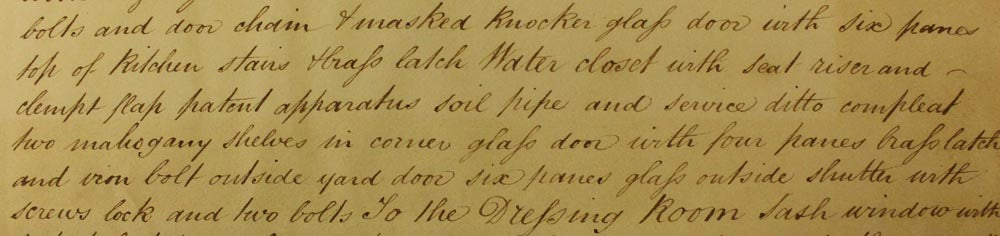

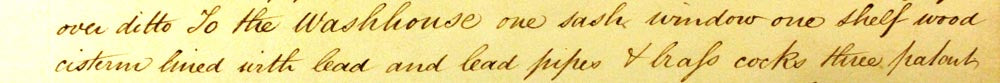

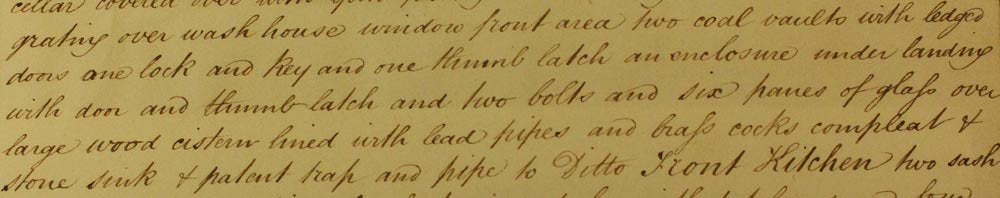

Much of what we know about water, waste and 48 Doughty Street comes from letters and legal documents in the Museum’s collections. A letter in the archive dated 18 March 1837 informs the property owner, Mr Banks that a ‘Mr C. Dickens’ has made an offer to rent 48 Doughty Street at £80 per annum for 3 years provided he paint the Drawing Room and the blind frames around the windows and clean the ceiling. These were agreed to, and the lease granted on 3 April 1837. On the schedule of property on the rental agreement, there are records for cisterns and pipes in the basement, demonstrating there was running water at the time of Dickens’s occupancy.

Record on the 1837 schedule of property for two lead-lined cisterns. Charles Dickens Museum Collection (B375).

Record on the 1837 schedule of property for two lead-lined cisterns. Charles Dickens Museum Collection (B375).

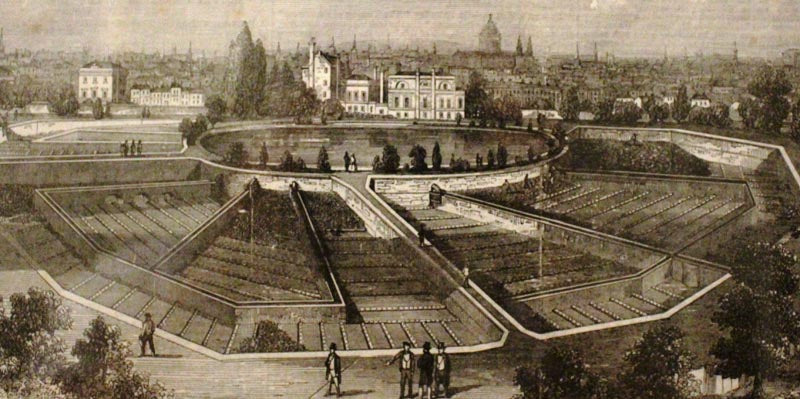

‘The New River Head Company’ was the likely water supplier to Doughty Street. They drew on springs at Chadwell and Ampthill and from the River Lea in Hertfordshire and ran them through to a large aqueduct ‘The New River Head’, southwest of Sadler’s Wells. Doughty Street was probably supplied with water from one of the New River reservoirs in either Stoke Newington or Clerkenwell.

New River Head Site

The water mains were turned on by turncocks at the top of the street for about two hours a day, and would fill up household cisterns via large, hollowed out elm wood pipes. Poorer neighbourhoods would have relied on communal pumps on the street or carriers who sold New River water by the bucketful on a casual basis.

No matter how you got water, the supply could be insufficient. There were issues with leaking pipes and water theft. In 1853, Dickens wrote to complain about the water supply to his current home, Tavistock House: “...my supply of water is often absurdly insufficient and although I pay the extra service for a Bath Cistern I am usually left on Monday morning as dry as if there was no New River Company in existence- which I sometimes devoutly wish were the case.”

Before filtered water was used, fish could sometimes be found in the pipes, including a dozen eels nearly two feet long reported in Pall Mall. The matter of water contamination was something that concerned Dickens, and it prompted the article ‘The Troubled Water Question’ in his journal Household Words.

Dickens placed a great deal of importance on cleanliness so a regular water supply was essential. In his later home at Tavistock house, he commissioned and designed a special ‘shower room’. Here at 48 Doughty Street, servants would have had to lug buckets of heated water up three flights of stairs to Dressing Room to fill his bath.

Dressing Room at 48 Doughty Street, including a hip bath, similar to the sort the Dickens family would have used when they lived here in the 1830s. Credit: Charles Dickens Museum.

So that is about water, but what about waste? 48 Doughty Street was built in 1807-1809, at a time when most middleclass houses would have had their own cesspit to contain household waste. It was the unfortunate task of Night Soil Men to clear out these brick chambers on a regular basis (they worked at night, lowering a ‘holeman’ in to shovel the waste into a tub and two ‘tubmen’ would empty the tub into a waiting cart. Occasionally, the holeman would pass out from the fumes).

The growth in flushing toilets increased the volume in cesspits and it became common for waste to find its way into the city’s main rainwater systems and waterways. No wonder, In a letter to his landlord in 1839, Dickens complains about the stench from the drains: “the drains...have been a serious annoyance to us, and although we have had the plumbers in the house half a dozen times, we have not been able to make them last our time without often receiving strong notice of their being in the neighbourhood”'

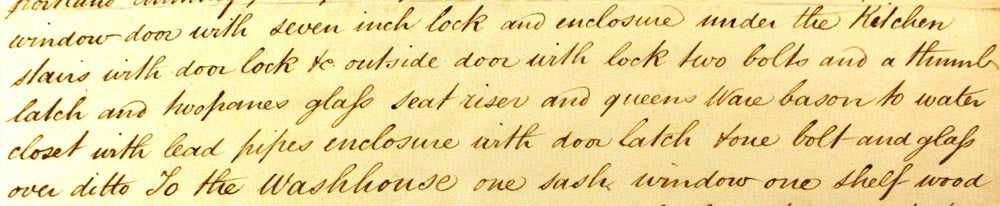

The 1837 schedule of property on the rental agreement lists two ‘Water Closets’, with patent apparatus, on the ground floor and in the basement of 48 Doughty Street. As well as these two toilets, the family would have used chamber pots or a commode, which would have been emptied by servants in the morning, probably down into the ‘WCs’.

Record on the 1837 schedule of property for two Water Closets. Charles Dickens Museum Collection (B375).

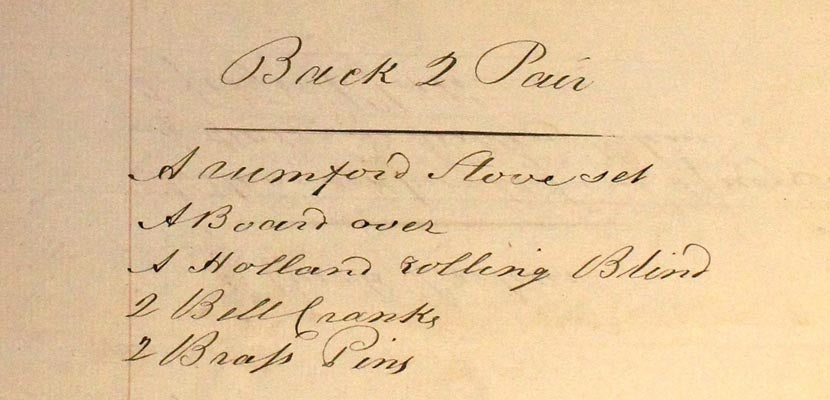

‘Bell Cranks’ are listed in the 1837 inventory and the remains of this bell system were discovered during the Museum’s 2012 refurbishment. The 48 Doughty Street bell system would ‘call’ servants to the aid of their master or mistress anywhere in the house. It is likely on hearing the bell from the kitchen, servants would have been summoned to carry human waste down five flights of stairs or lug buckets of hot water up for baths.

‘Bell Cranks’ listed on the Inventory of 48 Doughty Street, 1837. Charles Dickens Museum Collection (B374)

We hope, on World Toilet Day 2016, water and waste matters of 48 Doughty Street can remind us of the progress we’ve made in sanitation since the Victorian times, even as we also remember that we’ve got a way to go to improve standards globally.

By Louisa Price, Curator at the Charles Dickens Museum

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog