A Closer Look: the language of flowers

Denis Moiseev is collections intern at the Charles Dickens Museum and is completing his MA in the History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London. The internship was made possible with support from NADFAS.

By Denis Moiseev

In a world with over 6,000 spoken languages, it is easy to forget that language does not necessarily have to be limited to sentences, words and letters. Although language is primarily a method of verbal communication, in the case of computer code and sign language, it can also be distinctly non-verbal. Throughout the history of art, painters and draughtsmen left clues or symbols in their works to communicate ideas. Examples of this symbolic use of images can be found in our own collection, which means that we have to study our artworks carefully; even the smallest details can be significant. Some paintings, like our portrait of Katey Perugini, contain secrets that add a new layer of meaning to the work: secrets that can only be uncovered if you understand the language of flowers.

Portrait of Katey Perugini by Carlo Perugini (c.1874)

Pioneered by Aby Warburg (1866-1929) and later advocated by Erwin Panofsky (1892-1968), iconography, the identification of symbols and recurring motifs, became a branch of the academic study of art history. The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) by Jan van Eyck is perhaps one of the best early examples of the interpretations gleaned from an iconographic approach.

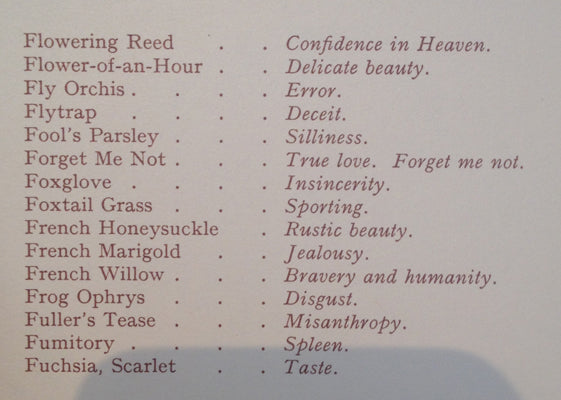

400 years after Van Eyck painted the Arnolfini Portrait, the Pre-Raphaelites continued using a secretive language to conceal meaning within a painting. Given the Pre-Raphaelite interest in replicating nature, flowers became the preferred motif for this purpose. Some of these meanings have not been lost – the rose remains an unwavering symbol of love – but many have been forgotten. The extent to which flowers were ascribed meanings is really quite surprising: entire books or A to Z’s detailing the meaning of flowers were compiled. From the early years of the nineteenth century, botany and flower cultivation became increasingly popular which naturally led to an increase in the publication of botanical volumes and with it, the use of flower arrangements to convey cryptic messages. The use of flowers in the communication of ideas and themes is sometimes referred to as floriology or floriography. John Henry Ingram’s (1842-1916) contemporary text, Flora Symbolica, is an interesting resource detailing the history of floriology and the meaning of certain flowers. Ingram went so far as to state that flowers speak ‘a language more powerful, and far more expressive than that of the tongue'. The Pre-Raphaelites were keen to carefully reproduce what they saw in nature, so they studied flowers as the botanists did. The result? Cryptic symbolism that a Victorian would recognise and understand, but we may overlook. Flowers can be seen everywhere in Pre-Raphaelite paintings,

from daffodils, roses and daisies, to poppies, violets and apple blossoms – they are an intrinsic part of their style and theme.

A book listing flowers and their meanings

Katherine Dickens (1839 – 1929), or Katey, was the second daughter and third child of Charles and Catherine Dickens. She demonstrated a keen interest in the visual arts and at the age of thirteen took lessons from Francis Cary, Head of the Bloomsbury School of Art. Katey was an accomplished artist and ultimately succeeded in exhibiting work at the Royal Academy. Notably, she also modelled for John Everett Millais on numerous occasions, including for The Black Brunswicker (1860).

Katey Modelled in John Everett Millais's 'The Black Brunswicker' (1860)

In 1874, Katey married Carlo Perugini, another artist associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, who painted the portrait hanging in the morning room soon after their marriage. Although their income was somewhat precarious and highly dependent on the sale of their pictures, Katey is depicted as fashionable and beautiful, wearing a black choker, pearl earrings and a silk dress. Unlike Perugini’s other paintings, this portrait of Katey seems naturalistic, markedly different from his usual style which was heavily influenced by Sir Frederic Leighton, his mentor. By looking carefully, we notice that Perugini included flowers in the painting: a rose in Katey’s bonnet, and a bunch of forget-me-nots in her dress.

Rose buds in Katey's bonnet & forget-me-nots in Katey's dress

Considering the prevalence of floriography and the circumstances surrounding the creation of the painting, it is likely that these flowers have a symbolic meaning. Traditionally, the pink rose and buds represent new love – a suitable symbol for a newlywed - while forget-me-nots symbolise true love and fidelity.

List of flowers and their meanings

Looking closely at paintings can be incredibly rewarding. Our painting of Katey Perugini is a great example of how small, cryptic clues can be hidden within a painting and how identifying and interpreting these symbols can help us better understand a work of art. In the case of our portrait, Carlo Perugini illustrates his undying love for Katey by carefully introducing flowers and their meanings into the composition.

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog