Dickens and the Spirit of Twelfth Cake Past by Pen Vogler

This year, the film The Man Who Invented Christmas has reminded us how much of a boost Dickens gave to our celebration of the festival, and how he helped to anchor the traditional Christmastide dinner of turkey and pudding to the day itself. Sadly, though, not even Dickens has been able to prevent his much-loved Twelfth Night from sliding into near-oblivion. Twelfth Night – the last day of Christmas – falls on 5th January but was often celebrated on 6th January; it is the day of the Kings, combining the church feast of Epiphany, when the baby Christ was revealed to the world in the shape of the three gentile kings, with elements of the subversive and rowdy Roman feast of Saturnalia, in which master and slave swap places. By the end of the nineteenth century, a pincer-movement of Queen Victoria’s disapproval of its riotousness and the Scrooge-like exigencies of commerce and industry squeezed the Twelve Days of Christmas down to three bank holidays. Dickens’s life shows us what we have lost; an opportunity for coming together for a last hurrah before the pinch of winter, for joy, drama, music, wassail and that great icon of Twelfth Night – the Twelfth Cake.

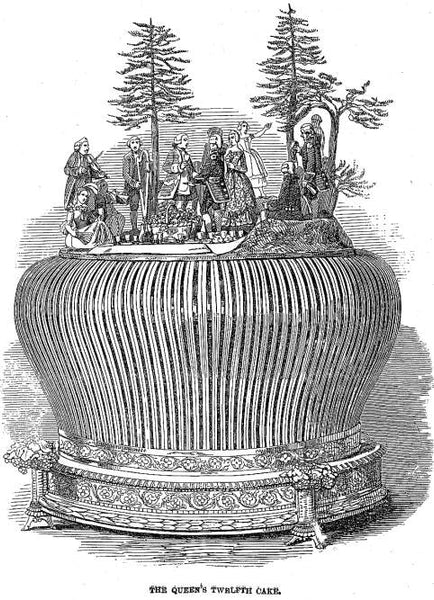

Queen Victoria’s Twelfth Cake, shown in the 'Illustrated London News', 1849. The cake was 30 inches across, gilded around its bowed sides, and displayed an elegant sugar-paste party enjoying a detailed sugar-paste picnic – a scene that provided a genteel antidote to the sort of riotousness the Queen disapproved of.

First recorded in England around 1570, by Pepys’s day it was a fully-fledged tradition; a leavened fruit cake, something like a cross between buttery Italian Panettone and modern Christmas cake; rich with the aroma of wealth and trade – cinnamon, cloves, mace and nutmeg. But what Pepys and his party are really interested in is what token they will get in their piece, for this is the character they get to play for the rest of the evening; a bean for the King, a pea for the Queen; perhaps, too, a clove for the knave, and a rag for the slut (the word having the seventeenth-century sense of ‘slovenly’ rather than our modern sense of ‘promiscuous’).

By the early nineteenth century, the bean and pea had evolved again to larger-than-life pantomime characters, printed onto cards. It was an opportunity for family theatrics and fun that hugely appealed to Dickens; he had happy memories of Twelfth Cakes and dancing at his school, before the terrible Marshalsea days, and delighted in recreating those lost joys for his own and friends’ children. Bean or no, Dickens was indubitably king of the Twelfth Night revels, recalled his daughter Mamie; he called on every one to join in the songs, recitations and theatricals; and “under his attentions the shyest child would brighten and become merry”.

The Victorian Twelfth Cake was no longer yeasted; all the air was beaten into the cake by the cook’s aching arm (as they were with all cakes until the miraculous raising agents later in the century). That magpie of social curiosities, William Hone, in his 1827 Every Day-Book describes them as “Dark with citron and plums and heavy as gold”; citrons are a sort of cross between a grapefruit and a lemon with added fragrance; ‘plums’ simply means dried fruit rather than specifically plums (as in ‘plum cake’).

Dickens’s friend Angela Burdett Coutts sent one to the family every year to mark both Twelfth Night and the birthday of her godson, Charley Dickens. Dickens once joked that it weighed ninety pounds. Many Twelfth Cakes are monsters; John Leech’s immortal illustration of the Ghost of Christmas present in A Christmas Carol, shows him with his foot resting upon one of the ‘immense twelfth cakes’, as though it were a white and pink pouffe.

Scrooge’s Third Visitor, the Ghost of Christmas Present, with his foot on one of the ‘immense twelfth cakes’ in the illustration by John Leech.

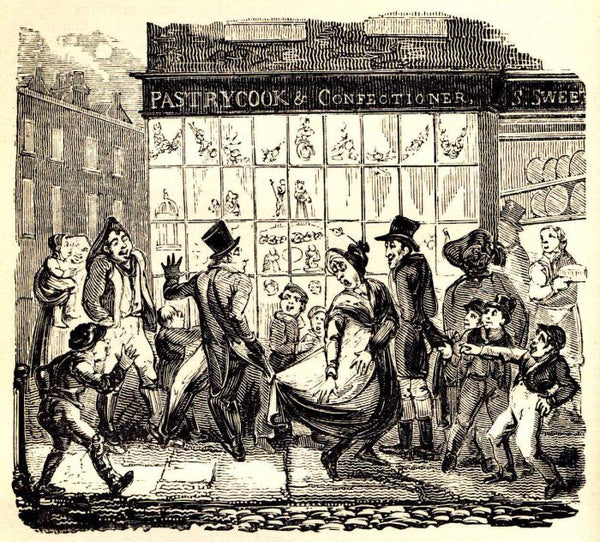

The ‘poor little Twelfth Cake’ in The Mystery of Edwin Drood earns Dickens’s pity for being rather ‘a Twenty-fourth Cake or a Forty-eighth Cake’. They need to be big, partly so everybody gets a treat and partly to have room for the confectioners to outdo each other in the intricacy of icing sugar decorations, made from the pliable Gum Tragacanth or Gum Dragon, coloured, supposedly, with natural dyes (though also poisonous mercury or copper). Hone describes them in the pastry-cooks’ windows, dazzling onlookers with their decorations of “Stars, castles, kings, cottages, dragons, trees, fish, palaces, cats, dogs, churches, lions, milkmaids, knights, serpents, and innumerable other forms, in snow-white confectionery, painted with variegated colours, glittering by ‘excess of light’, reflected from mirrors against the walls.”

William Hone reports that urchins would nail together the clothes of people admiring the Twelfth Cakes in front of the pastry cooks windows. ('The Everyday Book', 1825)

The impecunious Leigh Hunt, the original of Bleak House’s Harold Skimpole, shared Dickens’s understanding of how hunger could work on the imagination. ‘Even the little ragged boys, who stand at those shops by the hour, admiring the heaven within, and are destined to have none of it, get, perhaps, from imagination alone, a stronger taste of the beatitude, than many a richly-fed palate.’ It is hard to imagine, in our chocolate-obsessed twenty-first century, just how rare and exciting it was to have all the tastes in a rich fruit cake tumble over one another in the mouth – and how lucky we are to be able to afford them.

There was great pride in this British tradition and some bafflement that it hadn’t been exported. Thackeray, a frequent guest at Dickens’s Twelfth Night parties in London, finding himself in a ‘foreign city’ (Rome) in 1854, reported that ‘you could not even get a magic-lantern or buy Twelfth-Night characters’ for a children’s entertainment. Although many parts of France, Switzerland and Italy had – and still have – their own tradition of Epiphany cakes or King Cakes, they were not as grand as the Twelfth Cake which Angela Burdett-Coutts sent to the Dickens family when they were in Genoa in 1844/5. The local Swiss pastry-cook who was charged with the repair of a crack in its icing was so enchanted by it he showed it off to an eager group of townspeople. Dickens reported that ‘my good friend and servant who speaks all languages and knows none, renders it to the natives, pane dolce numero dodici – sweet bread number twelve’.

No Twelfth-Night party would be complete without the sort of ‘hot stuff from the jug’ that the Cratchits make merry with. In fruit-growing regions, wassail (warm, frothy beer with roast apples floating in it) was traditionally drunk to the health of the fruit trees on Twelfth Night and its association with the festival is recorded in Henry VII’s Household Ordinances; Dickens has it served at Dingley Dell at a Pickwickian Christmas. He had his own recipe for punch to make the cheeks glow; and the reformed Scrooge offers Bob Cratchit some expansive, post-Christmas Smoking Bishop, port mulled with spices and orange.

Dickens’s punch; he sent the recipe in a letter to a Mrs Fillonneau, promising it would make her ‘a beautiful Punchmaker in more senses than one’. Photography (c) CICO Books

After the diminution of Twelfth Night, the Twelfth Cake tokens, demoted to mere coins, strayed into the Christmas pud; the cake itself was downsized and billetted onto Christmas day although there’s no room there to accommodate it, and the night itself is marked by the gloom of taking down the Christmas decorations. This year, we should all defy Queen Victoria and modern capitalism. Make some hot stuff; invite Dickens in, along with some living friends and family. Accessorize your Christmas Cake with icing figures and slip some token in, play some games, forfeits, or act out a play… and welcome the Spirit of Twelfth Night past into your home.

Modernised recipes for Twelfth Cake, Smoking Bishop, Dickens’s punch and Wassail are in 'Dinner with Dickens' by Pen Vogler, available in the Museum shop.

Pen Vogler is a food historian and author of Dinner with Mr Darcy: Recipes inspired by the novels and letters of Jane Austen and Dinner with Dickens: Recipes Inspired by the Life and Works of Charles Dickens. Her day job is at Penguin books, where she edited Penguin’s Great Food series.

Museum Blog

This blog takes you behind the scenes at the Charles Dickens Museum, giving fresh insight on everything from discoveries new and old in our collection, to exhibitions, events and learning initiatives.

You’ll be hearing from a variety of Museum staff and volunteers, as well as guest curators, academics, artists and Dickens enthusiasts. Why not join the debate and let us know you thoughts on the latest blog by using our hashtag #CDMBlog